SLJ Radio #2: Marc Ribot at 70

Tracklist:

Marc Ribot, “Prelude #2” (Marc Ribot Plays Solo Guitar Works of Frantz Casseus, 1993)

Lounge Lizards, “Voice of Chunk” (Voice of Chunk, 1988)

Rootless Cosmopolitans, “The Wind Cries Mary” (Rootless Cosmopolitans, 1990)

John Zorn, “Maskil” (Bar Kokhba, 1996)

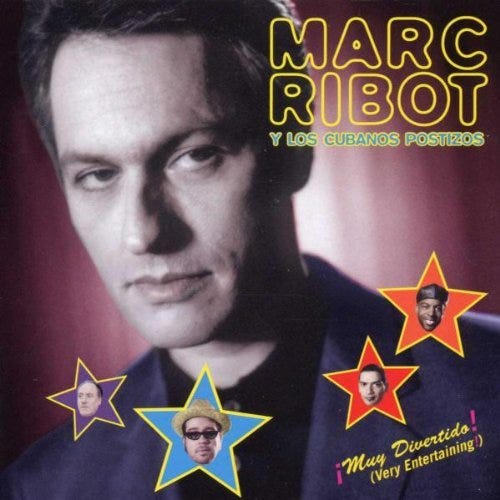

Los Cubanos Postizos, “Baile Baile Baile” (Muy Divertido!, 2000)

Marc Ribot, “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” (Saints, 2001)

Marc Ribot, “Earth” (Scelsi Mornings, 2003)

Dave Douglas, “Black Rock Park” (Freak In, 2003)

Ellery Eskelin, “Anywhere Not Here” (Ten, 2004)

Marc Ribot Trio, “Old Man River” (Live at the Village Vanguard, 2014)

Marc Ribot, “Delancey Waltz” (Silent Movies, 2010)

Ceramic Dog, “Take 5” (Your Turn, 2013)

Marc Ribot, “How to Walk in Freedom” (Songs of Resistance, 2018)

Marc Ribot, “Noise #2” (Don’t Blame Me, 1995)

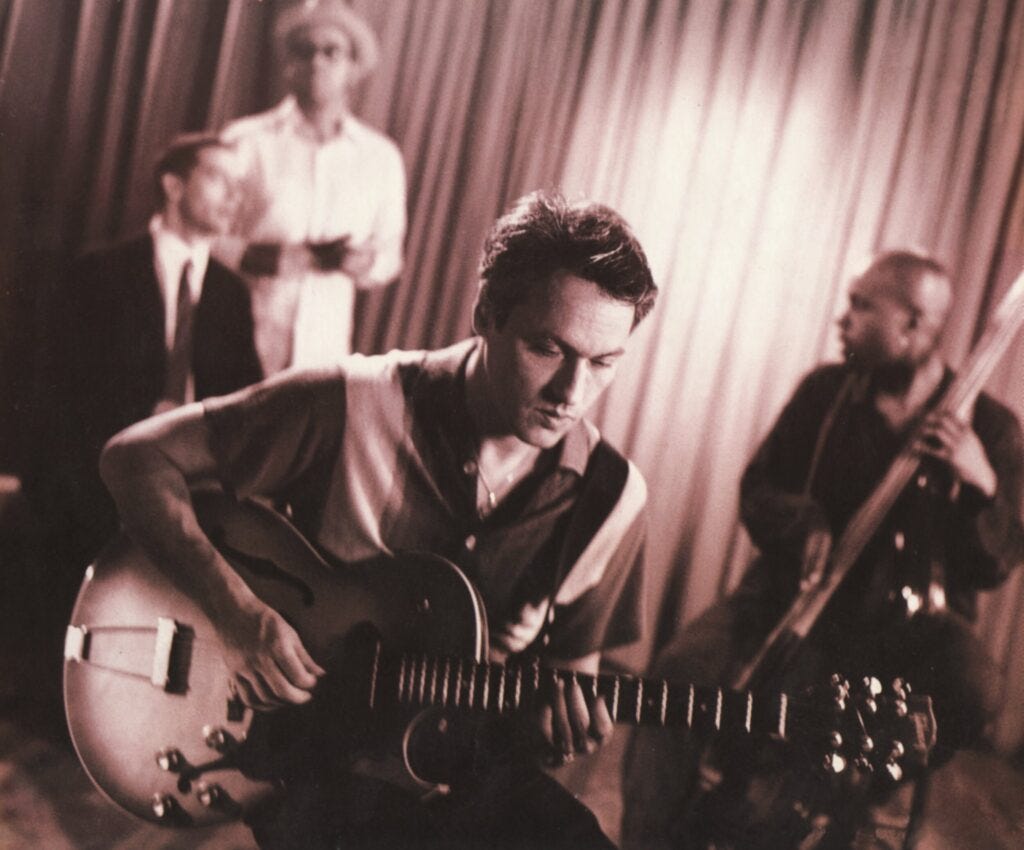

Marc Ribot turned 70 this year, He could be called an avant-garde-free punk-rock-jazz guitarist, but that would not do justice to the incredibly versatile and radically uncompromising nature of his work. In the subtitle of his recent book , Unstrung, he calls himself a “noise guitarist”. So let’s settle for that.

Ribot has led punk bands and jazz trios, composed pieces for film and dance performances, worked extensively as a session musician (redefining Tom Waits’ sound in the mid-1980s), and ventured into Jewish, Haitian and Cuban musical traditions. At the same time, his work has always been closely intertwined with (a certain strand of) jazz. Although it would be hard to classify Ribot as a traditional jazz guitarist, there is always a distinct and undeniable smell of jazz emanating from his music. In the short documentary film The Lost String (Anaïs Prosaïc, 2007), Ribot provides the key to a better understanding of his relationship with the jazz tradition:

“I think that a particular music can be part of more than one history. There is a certain trend in jazz, starting with Thelonious Monk, Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time band, and Albert Ayler, that can also be written into a history of rock. I have tried to imagine a history of rock that includes these musicians.”

In an attempt to five decades of Ribot’s radically genre-defying work into one hour, this episode takes Ribot’s experimental re-imagination and cross-fertilization of musical genres as a guiding principle.

1. Marc Ribot, “Prelude #2”, Marc Ribot Plays Solo Guitar Works of Frantz Casseus, 1993 [0’00”-1’06”]

As a prelude to this excursion into Ribot’s work, this “Prelude #2” takes us back to the very beginning of his musicianship. Ribot first picked up the guitar at the age of 10, when his parents asked a family friend to teach him the instrument. That family friend was Frantz Casseus, who had emigrated from Haïti to the US in 1946 and had become a close friend of Ribot’s father. As Ribot only found out later, Casseus was in fact “the Father of the Haitian classical guitar”, who had come to New York to compose guitar music that fused Haitian folk music with elements of the European classical tradition. One of his songs that made it to a broader audience was “Merci Bon Dieu”, recorded by Harry Belafonte on An Evening with Belafonte (1957), on which Casseus also plays guitar.

At the time of Casseus’ death in 1993, Ribot promised him to look after his work. And so he did. In 1993, after having taken more lessons from Casseus, he recorded a double album with solo pieces composed by Casseus (re-released in 2020 with three additional bonus tracks). When Haiti was devastated by an earthquake in 2010, Ribot founded the Frantz Casseus Young Guitarists Program in Port-Au-Prince. And 2014 saw the publication of Frantz Casseus Guitar Works, a new edition of Casseus’ guitar compositions co-edited by Ribot and Italian classical guitarist Alberto Mesirca. Ribot also devotes an essay to Casseus in his book Unstrung, discussing his teaching, his life in exile, and the fact that he never profited economically from his work.

Casseus’ teaching had a formative impact on Ribot’s playing. For one thing, Casseus taught Ribot to play the guitar right-handed, while Ribot is in fact left-handed. As he explains in an interview with Bill Milkowski, Casseus and Ribot’s mother gave two conflicting explanations for this decision. According to Casseus, Ribot’s mother told him that her son was just pretending to be left-handed, just to annoy her. According to Ribot’s mother, Casseus was just too lazy to change the strings on the guitar and assumed that Ribot would quit within a few weeks anyway.

Whatever the reason, Ribot designates this formative event as “the secret of my so-called style”. Realizing that he would never attain the virtuosity of the great jazz guitarists, he started to acknowledge the beauty of limitations. It’s an interesting thought to keep in mind while listening to the remaining tracks in this episode: Ribot’s playing does not so much pursue technical virtuosity, but rather explores the opportunities of a more economical playing and takes the freedom to employ less conventional sounds and techniques.

One jazz musician and composer who comes to mind here, and who indeed had a profound influence on Ribot, is Thelonious Monk. Like Ribot, Monk’s style is immediately recognizable because of the way he handles his instrument and develops his solos. The particularly unorthodox, percussive way of hitting the keys on his piano, the use of unconventional scales, the often sparse use of notes and unexpected pauses in his improvisations: these are all things that to an important extent reappear in Ribot’s playing and are part of his equally recognizable style.

2. The Lounge Lizards, “Voice of Chunk”, Voice of Chunk, 1988 [1’06”-6’22”]

In 1977, Ribot moved to downtown New York, which has been his musical biotope ever since. Ribot soon absorbed the influences of experimental guitarists like Fred Frith, James Blood Ulmer and, most importantly, Arto Lindsay. Lindsay had been a key figure in the 1970s New York “no wave” scene with his band DNA, which experimented heavily with noise and dissonance and produced often atonal blends of punk, funk and free jazz. On several occasions, Ribot has acknowledged the deep impact Lindsay had on his sound and on his non-technical and genre-defying approach to guitar playing. Ribot would later regularly collaborate with Lindsay, contributing to the latter’s recordings with Ambitious Lovers and playing with him in several projects by John Zorn. At one point in the 1990s, Lindsay even tried to extend his trio with Melvin Gibbs and Douglas Brown with Ribot and Bernie Worrell, but this band never materialized.

When Ribot became a member of the Lounge Lizards in 1984, he was in fact replacing Lindsay, who had been the guitarist in the band since its foundation by the brothers John and Evan Lurie in 1978 and who can be heard on their first self-titled album of 1981. For Ribot, the Lounge Lizards were “a kind of mutant reading of Thelonious Monk” and, together with the Jazz Passengers (the other band Ribot played in at the time), the band provided the breeding ground for his exploration of free improvisation and genre-crossing between jazz, punk, funk, and other genres.

On “Voice of Chunk”, the titular track from the 1989 Lounge Lizards album, the saxophones of John Lurie and Roy Nathanson produce waves that never really coincide, backed up by the laid-back rhythm of percussionist E.J. Rodriguez and drummer Dougie Bowne. Eric Sanko’s bass and Curtis Fowlkes’ trombone lay down a steady funky groove. This rhythmic and melodic flow is punctured by Evan Lurie’s occasional dissonant piano chord and, most poignantly, when Ribot’s angular and noisy guitar sound enters halfway through the song. Both in terms of sound and energy, Ribot’s solo derails the track until his notes are picked up again by the saxes, who realign the song again and lay it down in a repetitive exchange with the piano. To witness the band’s dynamic in a live context, see their performance on an episode on Night Music (fast forward through the slightly cringey exchange between Jools Holland and John Lurie at the beginning).

3. Marc Ribot, “The Wind Cries Mary”, Rootless Cosmopolitans, 1990 [6’22”-9’56”]

In 1990, Ribot recorded Rootless Cosmopolitans, his first album as a band leader. The title of the project was taken from a poem by Alen Ginsberg and refers to the term that was used under Stalin to refer to Jewish artists and intellectuals during the anti-semitic purges of the late 1940s. Not surprisingly, the band was again deeply rooted in the New York scene of the day. The horn section consisted of Roy Nathanson and Curtis Fowlkes, with whom Ribot had already played in the Jazz Passengers and the Lounge Lizards, joined by Don Byron on (bass) clarinet. The album also marks the first collaboration between Ribot and pianist Anthony Coleman, who would become a key figure in the New York avant-garde Jewish music scene of the 1990s and a regular contributor to projects by John Zorn. Three of the songs also feature Brooklyn-based Melvin Gibbs, who would also play in bands like Defunkt and the Rollins Band, and would become a regular bassist on Arto Lindsay’s records. Lindsay himself also appears on two songs, including the cover of Hendrix’ “The Wind Cries Mary”.

The essence of this cover of Jimi Hendrix’ “The Wind Cries Mary” is that it is in fact not a cover. Nothing of the music of the original remains. Instead Ribot recites the lyrics over a funk-noise groove driven by Gibbs’ bass and Lindsay’s rhythmic percussive guitar riff. Ribot’s tribute to Hendrix approaches him via an unexpected detour: it does not engage with the Hendrix’ techniques or style, but only with the lyrics of the song. As he explained in an interview, Ribot tried to capture the sense in which Hendrix “was a poet in terms of what he said and what he played” and to evoke that “something that surrounded the music that made it be great”.

4. John Zorn, “Maskil”, Bar Kokhba, 1996 [9’56”-14’30”]

John Zorn is without doubt one of the most influential and innovative musicians of the last few decades and, like Ribot, has without much comprise transgressed generic boundaries between jazz, punk, rock, metal, etc. Ribot first collaborated with Zorn on Filmworks VII: Cynical Hysterie Hour, a series of musical pieces for Japanese cartoons. The album was recorded in 1988 and 1989 (but not released until 1996) and also features Bill Frisell and Arto Lindsay, two other guitarists Zorn would regularly collaborate with. During the following two decades, Ribot will also play on other Filmworks albums and in other Zorn projects, such as The Dreamers (with Joey Baron and Trevor Dunn) and Moonchild (with Mike Patton). On Zorn’s The Book of Heads (1995) Ribot plays solo guitar using extended techniques such as rubbing balloons on the strings, pulling and hitting strings with pencils, etc.

Bar Kokhba (1996) is a double album with small ensembles playing rearrangements of the Masada project and is widely conceived as one of Zorn’s masterpieces. Initially, iconic Masada project consisted of a quartet (with Joey Baron, Greg Cohen, and Dave Douglas) playing compositions in which Zorn combined Jewish musical scales with Ornette Coleman’s approach to free improvisation. (The quartet played a legendary concert at Jazz Middelheim in Antwerp in 1999, which was later released on Zorn’s Tzadik label – and which will without doubt show up in one of the following SmellsLikeJazz episodes.) On Bar Kokhba, Zorn reconceived the Masada project for chamber ensembles with violin, cello, electric guitar, bass, clarinets, piano, trumpet, drums and percussion, which allowed him to foreground the harmonic texture of the music. “Maskil” (Hebrew for “instructive poem”, referring to the Psalms) is a duet between Ribot and bassist Greg Cohen, member of the original Masada quartet with whom Ribot had already played together in Tom Waits’ band. Employing Jewish scales, Cohen and Ribot create a melodic and serene piece in a stripped down arrangement. The song also appears as a duet between clarinet (Chris Speed) and organ (Jamie Saft) on Filmworks IX: Trembling Before G-D (2000).

5. Los Cubanos Postizos, “Baile Baile Baile”, Muy Divertido!, 2000 [14’30”-18’28”]

With Los Cubanos Postizos (“The Prosthetic Cubans”) Ribot released his first albums for a major label: both their eponymous debut of 1998 and the sequel Muy Divertido! (2000) were released on Atlantic and were overall positively reviewed by critics. Markedly different from Ry Cooder’s Grammy-winning Buena Vista Social Club, which was released in 1997, Ribot’s take on Cuban music takes it in a radically different direction by re-imagining it from a post-punk perspective. The Cuban music in this band is essentially prosthetic, i.e. artificial and man-made, rather than organic.

The core of the band consisted of fellow Jazz Passenger Brad Jones on bass, and Cuban musicians E.J. Rodriguez and Robert J. Rodriguez on drums and percussion. Anthony Coleman and Jon Medeski (only on the first album), feature as guests on organ and mellotron. Next to original compositions, the albums reinterpret compositions by legendary Cuban bandleader and mambo icon icon Arsenio Rodríguez (unrelated to the two Rodríguezes in the band). Rodríguez was the pioneer of the so-called “son montuno”, a subgenre of the “son cubano”, adding complex horn arrangements and often cyclical patterns.

In the late 1990s, concerts by Los Cubanos were popular New York City live events, and the albums established a lasting legacy. In 2011, the band reunited (with Horacio “El Negro” Hernandez on drums) and played several gigs at jazz festivals. And just a few weeks ago, in November 2024, they performed a sold-out show during a special weekend devoted to Ribot’s music by the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg.

As Ribot explains in an interview with Bomb magazine, the idea for Los Cubanos originated when his daughter was born and he hadn’t played much guitar. To reignite his playing, he conceived of a project centering on the music of Arsenio Rodríguez, to which he had been introduced years before by Anthony Coleman. Ribot immediately connected to the sound of Rodríguez’s playing on the trés, a Cuban three-stringed guitar, and to the way the sound of this instrument was distorted through its amplification. Ribot gathered a band around him for a benefit, which then grew into Los Cubanos.

“Baile Baile Baile”, an original composition by Ribot from the Muy Divertido! album, exemplifies Ribot’s reimagination of the Cuban son. With a steady Latin funk groove, the music is at the same time accessible and even danceable, while the sudden and compact eruptions of noise and Ribot’s angular, distorted guitar move the song beyond Cuban realms and into a punk-rock-noise improvisational feast. Very entertaining indeed.

6. Marc Ribot, “Happiness Is a Warm Gun”, Saints, 2001 [18’28”-22’48”]

The album Saints could hardly have been further removed from the exuberance of the Los Cubanos album that preceded it. Saints strips Ribot of all accompaniment and features him on solo guitar, producing a series of pieces that are as experimental and radical as they are delicate and contemplative. The listener is as close to Ribot as she can get. Try listening to the album on your own. It is like spending 50 minutes on a couch in Ribot’s apartment, listening as he is freely exploring songs, turning them inside out while harnessing their melodic beauty. Ribot at his most naked and uncut. In many ways, Saints is the sequel to the 1995 album Don’t Blame Me, on which Ribot had mainly played interpretations of jazz standards that had been covered by Thelonious Monk or Albert Ayler. Because that album was released on a Japanese label, however, it had received little critical attention in the US.

Saints is deeply drenched in the music of free-jazz icon Albert Ayler. Not only does it contain a series of covers of Ayler compositions (like the titulary song), it also breathes an Aylerean approach to melody and improvisation. Often paired to other free-jazz pioneers like John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, Ayler (like Coltrane and Coleman) created a very personal and singular musical mode. An often overlooked aspect of free jazz is that it not only signifies a freedom from existing structures, but also a freedom to produce new forms and sounds that were based on a musician’s very personal conceptions of improvisation. Ayler, for example, combined a free idiom with a raw and often noisy energy while never losing sight of melody and conventional musical forms like march melodies and gospel hymns. It is not hard to see why Ayler had such a deep impact on Ribot’s playing. On Saints as on many other albums, Ribot combines a similar radical improvisational freedom and generic openness with a punk-noise energy and a delicate sense for musicality and melody.

In fact, Ayler is the one key figure (together with Monk) who offers a closer insight into Ribot’s relation to jazz improvisation, and into his musicianship as such. Ayler’s influence on Ribot dates back to the 1980s, when it was passed on to him by Lounge Lizard leader John Lurie. When recording the Rootless Cosmopolitans album, pianist Anthony Coleman told Ribot his playing reminded him of Ayler’s 1965 Bells album, which subsequently became a reference album for Ribot. “Bells” was the first cover of an Ayler tune Ribot recorded (on the 1994 Shrek album), followed by “Ghosts” on Don’t Blame Me and “Saints” and “Witches and Devils” on Saints.

Ayler’s influence can also be heard on Ribot’s cover of “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” (the second Beatles cover he recorded, after “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” on Rootless Cosmopolitans). Not only in the way in which Ribot moves in and out of the melody, but also in his exploration of sound. Especially in the very final section of the song, Ayler’s spirit, which is subtly present throughout, is allowed to erupt in full force in a series of bended notes, clearly evoking Ayler’s saxophone. Lennon’s song, with its complicated rhythmical changes and generic switches (from pop to blues to doo-wop), provides a very fertile ground for Ribot to explore. This cover shows the remarkable scope of Ribot’s musicianship as a guitar player and interpreter. While the original song has a 10-second fingerpicking intro that subsequently dissolves into a multi-layered arrangement of instrument and voices, Ribot plays the entire song on solo guitar and draws out its full melodic, rhythmic and sonoric richness.

7. Marc Ribot, “Earth”, Scelsi Mornings, 2003 [22’48”- 26’54”]

The 2003 album Scelsi Mornings (a reference to Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi) collects a series of compositions Ribot wrote for dance pieces by Wim Vandekeybus and Yoshiko Chuma. “Earth” is one of six pieces that Ribot composed for Vandekeybus’ dance performance Inasmuch as Life is borrowed… (2000) With heavily distorted guitar and feedback Ribot creates a noisescape over thundering percussion by Los Cubanos drummer Roberto Rodriguez and dark electronica by Eddie Sperry. Juxtaposing noise with heartbeat-like electronic pulses, the piece showcases Ribot as a composer of experimental atmospheric soundtracks, other examples of which are collected on Shoe String Symphonettes (1997), Soundtracks Volume 2 (2003) and Silent Movies (2010).

Generally speaking, these pieces are much more contained and composed, with less room for improvisation and often with Ribot’s guitar in a less central position. As Ribot explained in an interview, Vandekeybus’ dance performance was already finished, so that he had to compose to existing dance pieces. Unhappy with the original results, he rerecorded the pieces after having performed them live on tour with Vandekeybus and included them on the album Scelsi Mornings.

8. Dave Douglas, “Black Rock Park”, Freak In, 2003 [26’54”- 31’46”]

Before appearing on Freak In, Ribot had collaborated with Douglas on several projects by John Zorn (both had also played in different constellations of Zorn’s Masada.) Also part of the downtown New York jazz scene, Douglas was (and still is) driven by a constant drive of experimentation and self-reinvention. On Freak In, he ventured into electronic jazz, with loops and programming provided by Jamie Saft and electronic percussion by Ikue Mori. “Black Rock Park” recreates the electronic jazz vibe of Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew era. While Joey Baron’s acoustic drumming is both sparse and incredibly powerful, Ribot’s guitar combines blues-rock licks (a subtle reference to John McLaughlin?) and shrieking sounds tearing through the horn section and conversing with Baron’s syncopated rhythms. Like on so many other songs (including the next one in this list), Ribot emerges as a musician who both plays at the service of a band leader and adds a sound and dynamic that becomes an essential part of the song’s make-up.

9. Ellery Eskelin, “Anywhere Not Here”, Ten, 2004 [31’46”- 37’18”]

Another New York-based avant-garde jazz musician with whom Ribot collaborated is tenor saxophonist Ellery Eskelin. In 1996 Ribot appeared on Eskelin’s The Sun Died, a tribute to saxophonist Gene Ammons and one of his most critically acclaimed records. The album Ten marked the ten-year anniversary of Eskelin’s core trio with keyboardist Andrea Parkins and drummer Jim Black. Eskelin invited three additional players to join them on these recordings: bassist Melvin Gibbs, vocalist Jessica Constable, and Ribot.

“Anywhere Not Here” is a duet between Eskelin and Ribot, a delicate conversation between Eskelin’s unique phrasing and Ribot’s alternation between harmonics and atonal fragmentation. Ribot switches to a clear and full guitar sound (which he immediately changes back to dirty distortion on the next track, “If So”) to add the right colour to the music, as guitar and sax alternatively take the lead and back each other’s improvisations.

10. Marc Ribot Trio, “Old Man River”, Live at the Village Vanguard, 2014 [37’18”-43’40”]

In June 2012, Ribot played the legendary New York jazz club The Village Vanguard with Henry Grimes on bass and Chad Taylor on drums. The playlist included Albert Ayler’s “The Wizard” and “Bells”, Coltrane’s “Dearly Beloved” and “Sun Ship”, and two standards. Eight years before, the trio (with the addition of Roy Campbell on trumpet, who had died earlier in 2012) had recorded the album Spiritual Unity, named after Ayler’s 1964 album. Ribot described the trio as “some kind of weird punk-rock band disguised as playing the music of Albert Ayler.”

The concert was historical in more than one way. For Ribot, performing as a leader of a jazz trio at the Village Vanguard signalled the definitive acknowledgment of his stature as a jazz musician, as he followed in the footsteps of many jazz greats, most notably John Coltrane and Albert Ayler. Ayler played the Village Vanguard in 1966, a concert partly released on Impulse, after Coltrane pushed the label to release Ayler’s live music (rather than a studio album). Ayler played with two bassists that night. One of these bassists was Henry Grimes. In an almost miraculous turn of events, Grimes returned to the Village Vanguard stage with Ribot and Taylor some 46 years later.

After playing with Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Cecil Taylor, and other avant-garde jazz icons in 1960s, Grimes completely disappeared from the jazz scene at the end of the decade. Assumed dead (and reported as such on several occasions), Grimes had in fact been living in poverty in Los Angeles, after a trip to the West Coast to play with Al Jarreau and Jon Hendricks had gone wrong and he ended up selling his bass and losing touch with the jazz scene altogether. When a social-worker-cum-jazz-fan discovered Grimes in 2002 living in a tiny apartment, fellow jazz musicians helped him get back on the music scene and move back to New York one year later. William Parker, that other freejazz bass legend, donated an olive-green bass, on which Grimes can be seen playing on many occasions (for example in this duo performance with saxophonist Kidd Jordan at John Zorn’s The Stone, on the occasion of Grimes’ 75th birthday). When in 2007 Signs Along the Road, a collection of poetry by Grimes, was published, Ribot wrote the introduction (which was subsequently reprinted in Unstrung). In the last two decades of his life, Grimes played more than 600 concerts in more than 30 countries, collaborating with other jazz greats as Andrew Cyrille, Marshall Allen, Rashied Ali, Cecil Taylor, Wadada Leo Smith, and Dave Douglas.

The inclusion of “Old Man River” on the playlist that evening at the Village Vanguard was no coincidence. Ayler covered the song on his 1964 album Goin Home, with Grimes on bass. As Ribot explains in an interview with Paul Olson, he considers Goin Home as a key record for his own musical development and sees Grimes on that album as creating a wholly new role for the bassist and crafting a new kind of collective improvising. As he says about Grimes’ performance on the record: “It’s tempting to write off the density of his playing as just him going off the deep end, but when you listen to it, you hear the melody of the tune you’re playing sped up, counter-pointed, harmonized, attacked, distorted, played backwards.”

“Old Man River” is a jazz standard written by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II for the 1925 musical Show Boat and was one of the first musical pieces to feature a bass solo. Also on this version, Grimes delivers a solo. It is interesting to note how Grimes plays much more melodically than on the other songs. While the trio indulges in highly energetic and radically free group improvisations in their Coltrane and Ayler covers, on “Old Man River” they not only quiet down (note how the audience is still talking when Ribot’s delicate solo intro silences them), but also allow more room for melody, as they move in and out of the theme. Also Grimes, who explores a whole range of sounds throughout the concert, can be heard playing a beautifully delicate solo that captures the melodic beauty of the song.

Together with the trio’s studio album Spiritual Unity, Live at the Village Vanguard is a unique historical document of an extraordinary meeting of musical minds. Ribot is allowed to step into the 1960s free jazz scene to meet his musical ancestors, and, vice versa, Grimes is beamed into to the 21st century to join Ribot’s unique blend of punkrock and free improvisation. About his own guitar playing on the two albums, Ribot remarks that the translation of Ayler’s music to guitar created “a new meaning” that upset traditional boundaries between musical genres: “I knew that bringing the Ayler material into guitar was going to change it and also change the guitar. I knew when I played that material on guitar it was going to mess with some people’s assumptions about what ‘jazz’ is as well. People who would only listen to a certain type of punk rock would find themselves being moved by an Albert Ayler composition.” (Interview with Paul Olson)

11. Marc Ribot, “Delancey Waltz”, Silent Movies, 2010 [43’40”- 46’52”]

“Delancey Waltz” is the third solo piece included in this tracklist. It appears on the 2010 album Silent Movies, a collection of pieces Ribot composed for movies (or, as he explains in the liner notes, for movies he turned down but found himself writing for anyway, or for movie projects that only existed in his head).

Film music is a genre Ribot has regularly engaged with throughout his career. He can be heard on more experimental instances such as John Zorn Filmworks, but also on soundtracks of mainstream movies, including the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line (2005) and Martin Scorsese’s The Departed (2006).

“Delancey Waltz” was one of the pieces Ribot composed for the unreleased film Drunk Boat by JD Foster, who also produced the record. Foster’s production is an essential part of the music: he recorded the music in such a way that we hear both the acoustic ring of Ribot’s guitar strings and his amplifier. This semi-acoustic sound perfectly underscores the fragile, melancholy mood that dominates most of the tracks. Ribot’s playing is at its most naked and lyrical here, and even in the absence of film evokes images and atmospheres. As Ribot explains in the liner notes, he is exploring “the strange area … between music and visual image” (and adds that the album “might have better been titled Blind Movies, but that wasn’t as catchy”).

12. Ceramic Dog, “Take 5”, Your Turn, 2013 [46’52”- 52’16”]

Ribot’s latest band project, Ceramic Dog, is him saying “Fuck it, I’m just going to do a rock band.” (Interview with Bill Milkowski). The band originated when Ribot was approached by bassist and multi-instrumentalist Shahzad Ismaily (who also collaborated with Arooj Aftab, Vijay Iver, and many others) after one of his concerts. Ismaily suggested they form a trio together with drummer Ches Smith, with whom he played together in Trey Spruance’s Secret Chiefs 3.

If you caught Ribot live in Belgium the last few years, chances are that you saw him perform with Ceramic Dog. The trio is essentially a live band, as their uncompromising punkrock noise is at the same time driven by riff-based grooves and unpredictable improvisation. On the six albums they released so far, Ceramic Dog mostly play their own material, ranging from head-on three-chord rock to more complicated compositional pieces. Ribot also emerges on these records as a songwriter and lyricist, producing lyrics that balance between deadpan humour and aggressive activism. The albums also contain collaborations with Arto Lindsay, James Brandon Lewis, Syd Straw, and many others.

“Take Five” is one of the few covers by Ceramic Dog (another noteworthy cover is The Doors’ “Break on Through”, which opens their 2008 debut album, Party Intellectuals). It was released on the album Your Turn (2013), shortly after the death of Dave Brubeck, who turned Paul Desmond’s tune into a classic in 1959. But this turn of events was only coincidental. Ceramic Dog picked up the song after they noticed they were constantly being booked at jazz festivals, but actually played punkrock rather than jazz. When they tried to come up with a jazz standard they could play, they ended up with “Take Five”, one of the most widely known and iconic jazz tunes.

From the “1-2-3-4” count-off, “Take Five” is immediately sucked into the Ceramic Dog universe. The song opens with dirty and dissonant chords over a steady bass line and one of Ismaily’ samples. When the theme and bridge appear, they are immediately shredded into fragments and dissipate into dissonant chords again. Halfway through the song, the band enters into full improvisational mode. Smith freely abandons the beat and breaks down the song’s firm rhythmic structure, opening a space that Ribot fills by dissolving the theme into an atonal noisescape. Finally, Ismaily’s bass and samples reenter to lay the song down again. To experience the actual force of this improvisational drive behind Ceramic Dog, watch some of the live versions of this track online. Each version is radically different, morphing the song from ballad to straight funk back into noiserock.

13. Marc Ribot, “How to Walk in Freedom”, Songs of Resistance, 2018 [52’16”- 57’58”]

The album Songs of Resistance, 1942-2018 resulted directly from the election of Donald Trump in 2016. It is, as Ribot clarifies in his liner notes, his act of resistance as a musician. Ribot dove into the history of political music, from the Italian anti-Fascist resistance, the US civil rights movement to Mexican protest ballads, while also composing his own songs based on things he heard at demonstrations or in the press. All the songs on the album, Ribot emphasises, “were written and performed, without apology, as agitprop”. Profits from the recording were donated to the Indivisible Project, a grassroots movement defending American democracy against Trump’s political agenda.

Next to many of Ribot’s regular collaborators (Chad Taylor, Kenny Wollesen, Ches Smith, Shahzad Ismaily, etc.), the album also features a wide range of guest artists. In Ribot’s arrangement of the Civil Rights protest song “We Are Soldiers in the Army”, Fay Victor’s voice is accompanied by James Brandon Lewis’ saxophone. Tom Waits accompanies himself on acoustic guitar on his rendition of the anti-Fascist partisan song “Bella Ciao”. And on “The Militant Ecologist”, Meshell Ndegeocello, with Marc Feldman and Eric Friedlander on strings, delivers a hauntingly delicate version on another arrangement of an anti-Fascist song, “Fischia Il Vento”.

“How to Walk in Freedom”, one of Ribot’s own compositions, references Civil Rights activists Rosa Parks, Emma Goldman, and Malcolm X. It is a duet by Fay Victor and folk singer Sam Amidon, carried by Roy Nathanson’s spiritual jazz flute, Reinaldo de Jesus’s congas, Kenny Wollesen’s vibraphones, and Rachel Golub and Dave Eggar’s strings. The song perfectly illustrates a central tenet of Ribot’s musicianship: while it crosses generic boundaries, it firmly embeds Ribot’s creativity in a powerful and enriching collaborative practice that takes his music in new directions.

14. Marc Ribot, “Noise #2”, Don’t Blame Me, 1995 [57’58”- 59’12”]

Perhaps the best way to exit Ribot’s musical universe, is to listen to him working with one of the raw materials at the heart of his music: noise.

Both during live concerts and on some of his solo recordings, Ribot includes compositions and improvisations with only noise, crafting noisescapes that allow space and time for distorted sounds to unfurl, digress, expand, and morph into different shapes and forms.

Noise is very much at the centre of Ribot’s artistic endeavour. Like all great modern artists, Ribot dwells in the material dimension of his art, experiments with it, and puts it at the centre of his artistic practice.

In fact, Ribot has written extensively about noise and many other aspects of his music, such as his influences, artist’s rights, and life on tour. Should this episode leave you hungry for more of Ribot’s thoughts on music, check out his essays collected in Unstrung. Rants and Stories of a Noise Guitarist (2021).